| Home | Manuscripts | Top-10 Lists | e-World | Site Index |

|

The Best of Sherlock Holmes |

www.bestofsherlock.com/movies/1950s-tv-history.htm

Holmes and the Snake Skin Suits:

Fighting for Survival on '50s Television

By Russell Merritt, September 12, 2019 (revised)

Abstract

The release of the Rathbone-Bruce Sherlock Holmes series on television in May 1954 was a landmark in the use of studio film libraries on TV. The breakthrough marketing of this vintage series on TV led to the era of film classics screened on late-night television. Matty Fox, who rescued the Rathbone-Bruce series from the studio vaults, went on to market the first Sherlock Holmes series made for American TV, which starred Ronald Howard.

Introduction

It is a tale madmen used to tell in the King Cole Bar, under a gigantic cartoon mural; a story for territory salesmen at the all-night delis in L.A. or at Fritzel's in Chicago. You could have read about it in Billboard or Sponsor, but not in The Baker Street Journal. In academic talk, it will lose its essential fragrance, sound a little sterile, turn into a bland little report about suits… unfamiliar middle men, advertizing executives, Hollywood players, and long-forgotten fights over feature films on television.

But listen. Odds are you have never seen a Basil Rathbone-Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes feature in a movie theater. Almost certainly you never saw one as a double feature with a cartoon and newsreel.[1] Instead, you discovered those films on television or, if you are under a certain age, on a digital screen where you likely streamed it.

This is the way we encounter most classic Hollywood films today, on TV screens and monitors where they have been revived since the mid-1950s, and where their current reputations as cultural icons have been created. Like The Wizard of Oz, It's A Wonderful Life, or virtually any B-film noir prized today, the Universal Sherlock Holmes movies were rehabilitated in critical and popular esteem only on TV, emerging from the lukewarm reception critics gave them on their original release to find their abiding audiences among viewers brought up on late-night shows and matinee theaters.

How Sherlock Holmes migrated from motion pictures to television has seldom been told, and for good reason. Today, when films move seamlessly from theaters to home screens, the transition seems automatic and unremarkable.

But there was nothing inevitable about it in the early 1950s. Watching Sherlock Holmes movies on TV was made possible only by a series of cut-throat battles and shrewd calculations made over a short but remarkably eventful period of months. And when the films eventually emerged on television, the response ranged from delight to derision that passed into contempt.[2]

Feature Movies on TV in the 1950s

Part of the mockery stemmed from the debased conditions under which the films were broadcast, conditions that today beggar the imagination. For a generation that had only seen movies projected in movie theaters [the one place you could see features, pre-TV], the new screen resembled a grotesque parody of a show place, where movies from a different era were strangely resurrected as contorted ghosts of their original 35mm selves.

Sherlock Holmes on a 1950s TV Screen

The pictures were so snowy, small, and unstable that a viewer could hardly see what was happening. Scenes were brutally cut or condensed to make room for local commercials. Today, we are still familiar with commercial breaks. But not the slicing up of the films to fit into hour-long time slots, nor with black and white images that wriggled and waved with interference patterns, or lost all depth when pasted onto ultra low-resolution screens.

"How do you snip out 30% of a carefully made product and have it make sense?" the writer in a 1950 trade journal asked. His solution: "First, eliminate all dark scenes that won't show up on a TV tube, and then all the long shots in which distant objects get lost."[3] How to enlarge an image on a family TV set that could measure as little as 12" diagonally? Buy a specially designed magnifying glass that could be fit in front of the screen.

And yet, particularly for those who had never seen 1930s and wartime films, they could be mesmerizing. A lost world had opened up, and it is a tribute to many of those films, including the Rathbone-Holmes series, that their pull could be so strong they survived even these conditions. And of special importance to Sherlockians, it was through this deeply flawed medium that the last and most famous of the Sherlock Holmes feature film series was kept alive.

The First Sherlock Holmes Feature on Television

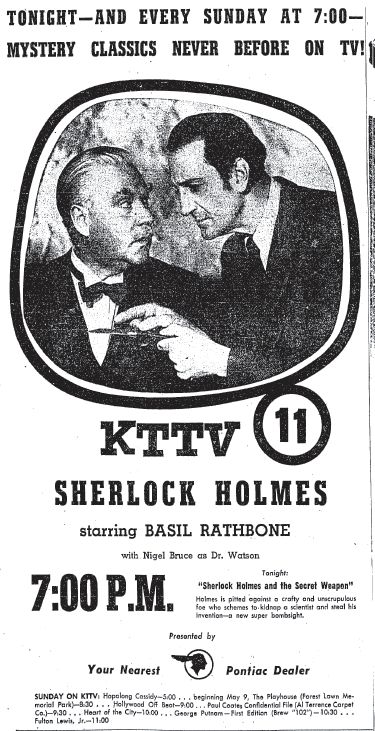

The series debuted over KTTV in Los Angeles on May 2, 1954: as best we can tell, the first time any American Sherlock Holmes feature was televised anywhere in the U.S.[4] Here is the advertisement in the Los Angeles Times that provided the details. As Holmes might have said, there are several points not entirely devoid of interest.

Holmes debuts on independent station KTTV

Los Angeles Times, 2 May 1954

Tonight's title, as the ad indicates, is Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon – the second film in the original series. It is being broadcast not in the off hours customarily given to old films, but in prime time on a Sunday night, in the spring of that fateful year 1954. It is also being broadcast over an independent station, not a network affiliate. Just as striking, it was sponsored by "Your Nearest Pontiac Dealer," – a consortium of local dealers – not by the national giant that owned the Pontiac brand, General Motors. And finally there is the Universal logo – significant because it is nowhere to be found, either in this ad, on any televised print, or in any promotional material.

What all this points to is a turning point in film exhibition, a curious mix of the old and new, with a studio still shy about acknowledging its involvement in the telecast of its own product, and an old movie still being shown by a local independent station when networks wanted nothing to do with movies in prime time. And yet there are quiet innovations: a movie being offered on prime time, underwritten entirely by a single sponsor in a top broadcast market. We are not just at the start of an important Sherlockian revival. The ad also doubles as a snapshot of a pivotal point in the rapidly changing relationship between film studios and a looming monster market.

A Pivotal Year in the History of Broadcasting Films on TV

In 1954, the famous freeze in the relations between Hollywood and the broadcast industry was in the midst of a great thaw, and the on-going battle over whether to reissue the studios' vintage A-list movies on television was coming to a head. And though Universal's Sherlock Holmes series was emphatically a B-list series, it played a curious and crucial role as a wedge in that on-going drama.

By the mid-50s there was, of course, nothing novel in re-running old films on TV. From virtually the start of commercial television, stations were notorious for filling their schedules with cheaply-made westerns, crime films, serials, discarded British imports, and cartoons from poverty-row studios. Even major studios – notably Universal, Paramount, and Twentieth Century-Fox – were surreptitiously putting many of their B-pictures, serials, and cartoons on the market.

Nor was there anything new about showing quality films on television. As early as 1944, David O. Selznick's Nothing Sacred (1937) with Carole Lombard and Fredric March and RKO's The Hunchback of Notre Dame had run on New York's WNBT. And in 1950, A Star is Born (1937) could be seen on WPIX, the same year Ford's Stagecoach (1939), Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent (1940), and Lubitsch's To Be or Not To Be (1942) were syndicated as part of a package of features produced by Walter Wanger and Alexander Korda.[5]

But these broadcasts were all under-the-counter, one-time only arrangements – covert operations where, to disguise their involvement, the major studios created sales through dummy companies, third parties and specially created studio subsidiaries whereby they could secretly engineer repurchase agreements. In virtually every case, the contracts required that studio identifications and logos be removed from all prints before they reached the air.[6]

The idea was to take advantage of the windfall profits made possible with one-off TV rentals without offending their theater chains and, in particular, independent exhibitors who saw in the rise of television the principal cause for the decline of theater attendance. Despite the on-going process of divorcing themselves from their theaters, mandated by the famous 1947 Supreme Court decree, the majors were still eager to maintain the good will of independents and the most powerful exhibitors who were still capable of boycotting studio product.

Breaking Film-TV Barriers with Sherlock Holmes

Universal was testing the water

with their Holmes series – going further than any studio had before in defying

the theaters by openly selling TV rights to their most marketable detective

series. With no theaters of their own to worry about, Universal was less

vulnerable to reprisals than other majors, and the studio was gambling that the

TV rentals would earn enough money to offset resentment from their peers. To

limit the risk, Universal confined their sales to the Sherlock Holmes series,

and as a precautionary measure hacked the company logo and other studio tags

off their prints in the prescribed manner. Further still, they discreetly

limited their series to selected markets – Los Angeles [KTTV], Tijuana [the

bi-lingual XETV], Cincinnati [WCPO], and Fresno, CA [KJEO], plus a few others.

But within the trade itself, they made no secret of the sales. Trade journals

reported them as Universal deals, while the company placated their critics

reassuring them that while they were authorizing these licenses, the Sherlock

Holmes broadcasts were "in no way indicative that Universal-International [Universal's

successor company] will reverse its ban on releasing the U-I backlog of

theatrical features to TV."[7]

Though only two films in the series were officially re-issued in theaters, Universal-International

thought the series showed promise in a medium still starving for product.

Why Holmes? Available business records and correspondence are silent on the subject, so any answer must remain speculative. Given the popularity of TV crime and mystery series, Holmes must have seemed a plausible choice. As John McElwee and Jack Tillmany have pointed out, 20th Century Fox had already released their Charlie Chan films on television a year earlier, and Paramount was ready to make its Bulldog Drummond series available just as Holmes made his TV screen test.[8] Further, the Rathbone-Bruce films were likely considered the logical bridge between Universal's long list of fillers that had already been snuck onto TV, and the company's most valuable pre-1947 properties.

The studio would not be willing to trade their prized assets – their famous '30s horror films, their Deanna Durbin musicals, and prestige pictures like Shadow of a Doubt, All Quiet on the Western Front and Destry Rides Again – until the tail end of the decade. But among their B-series, the Sherlock Holmes was the studio's tallest tent pole. Other poles – notably, Abbot & Costello and the Maria Montes/ John Hall fantasy series – had been taller when they were new, but by the mid-50s they were considered moth-eaten, banished to theatrical kiddie matinees.

Universal Studios Sells its TV Rights to Holmes

In any event, the test was sufficiently successful [ie, healthy sales; no significant blow back] that a few months later, the company took the next step, selling their Sherlock Holmes films outright. In summer 1954, James A. Mulvey [he, who with Walter O'Malley, owned the Brooklyn Dodgers, and with Samuel Goldwyn, owned Goldwyn Pictures] bought the series for himself, along with several Universal serials and a few second tier Walter Wanger productions – and authorized a national release.

With that sale, the Rathbone-Bruce series was now ready for major markets across the country. By fall, the films debuted on the country's most prominent network affiliates – CBS' principal branch in Philadelphia [WCAU], its flagship station in New York [WCBS] and then, in December, over DuMont's Chicago affiliate, WGN-TV.[9] No network would as yet televise a theatrical feature nationally – certainly not a B-picture. But their affiliates, even their flagship stations, were willing act on their own after seeing the ratings and revenues that independent rivals earned.

Holmes makes his Chicago debut on DuMont network affiliate WGN-TV

Chicago Tribune, 2 Nov 1954

In short, within a year, Sherlock Holmes had migrated from independents to three separate network stations in Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago. Within that year, too, Universal had come out of the closet as the ultimate author of the sale, determining that the risk of retaliation from ever-weakening independent theaters and chains, disinclined to fight over B-picture filler, was off-set by the ever-increasing profits from television syndication. Growing TV audiences meant ever-increasing paydays for a studio renting out old films that otherwise had virtually no commercial afterlife.

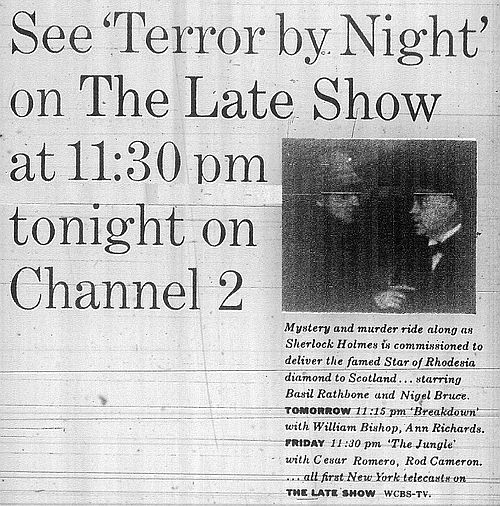

Holmes in New York, WCBS-TV

TV Guide 1 Dec 1954

Hollywood Dealmaker Matty Fox and Film Libraries

And yet, it is a sign of the turbulent relations between studios and this new market that Universal still insisted on shielding itself with dummy companies and third parties should they require deniability. Instead of releasing their Holmes films themselves, they – and then Mulvey – outsourced the series to innocuous-sounding companies controlled by an egg-shaped man little known outside the industry.

He is worth our attention. True, Mathew "Matty" Fox did not keep the Rathbone series alive out of love for Sherlock Holmes. But the series could have found no sharper, better qualified champion. Known for his steel nerves and razor-sharp intelligence, Fox was the consummate Hollywood player – arguably the most important figure in the history of film libraries.

Eventually, Matty Fox would revolutionize the way studios used their vaults, demonstrating how to use libraries to finance current film production. While a vice president at Universal, he had taken the distribution of old films to a new level, outsourcing the sound library to a theatrical film distributor called Realart Pictures in a deal that made millions for Universal. Two Sherlock Holmes films were part of that group, Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon and The Scarlet Claw, routinely reissued to sub-run theaters and drive-ins at the tail end of the 1940s.[10]

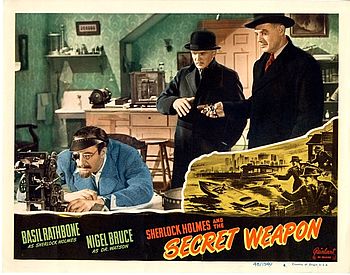

Reissue Lobby Cards: Realart, 1948

Only two Universal Sherlock Holmes films were ever officially reissued theatrically after the war, usually paired with each other on a double bill.

Having masterminded deals that were credited with revitalizing Universal, Matty Fox was now setting up companies of his own, and in 1954 engineered the most spectacular studio sale of the decade. He will show up continually in the Holmes television saga, the hidden hand behind the Rathbone-Bruce broadcasts, as he had been the catalyst for their short-lived theatrical reissue, and as he would become the link to the first Holmes series made for TV, starring Ronald Howard and H. Marion Crawford.[11]

Conan Doyle Estate and Universal's Rathbone Movies

Had it not been for his elaborate machinations, in fact, it

is likely the Universal series would have died in the vaults. The original

contracts Universal signed with the Conan Doyle estate stipulated that the

company's rights to the stories terminated in 1952 and that "immediately

after said date" Universal was to withdraw the film from distribution and

destroy all negatives and all exhibition prints.

The contracts also contained

provisions that specifically forbade TV broadcasts. To quote the agreement for

Terror

by Night, "[Universal] may announce but may not exhibit or

dramatize the photoplay by television. [Universal] may announce but not

dramatize said photoplay on radio. "[12]

One function of Matty Fox's web of intermediate companies was to skirt the

enforcement of those initial contracts.

Unfortunately, no subsequent literary rights agreement between Universal or Fox's companies and the estate is available, but the few clues that survive indicate that Arthur Conan Doyle's sons simply found themselves lost in the maze that Fox had created. In any case there is no evidence of any litigation directed against Universal-International or Fox's companies; nor is there any evidence that the estate – notorious for its litigious enthusiasms – saw any additional revenues from the television broadcasts.

Regardless, the timing of those broadcasts could not have been better. Matty Fox's Motion Pictures for Television [MPTV] acquired the TV rights from James Mulvey, just as Matty Fox's Western Television Corp [WTC] had bought them from Universal-International, and then sold them to a Matty Fox spin-off, Associated Artists Productions [AAP], run by one of Fox's former business partners. And even as he was selling and bartering licenses to stations, the dam was about to break, with top-line Hollywood movies set to flood the airwaves.

The R.K.O. Radio Pictures Sale to Thomas O'Neil and WOR-TV

A few weeks before Holmes' appearance in New York [9 Sept 1954], Matty Fox was engineering his greatest coup, and the most consequential of his many deals: arranging the $25 million sale of Howard Hughes' R.K.O. Radio Pictures to Thomas O'Neil, owner of WOR-TV and two regional networks.[13] With that sale, finally consummated July 1955, O'Neil came into possession of some 760 features that he could then supply to WOR's daily movie program, Million Dollar Movie. Treasures included classics like King Kong, Citizen Kane, Hitchcock's Notorious, John Ford's The Informer, films starring Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant, Fred Astaire musicals, and all the Val Lewton horror films.

Matty Fox immediately bought territorial rights for the markets O'Neil didn't control and spun those off to a sub-distributor called C&C Television Corp, which included a window for broadcast over the ABC network. With that, R.K.O.'s A-line product became available to every TV station in the country, and other major studios rushed to follow suit. Fearful that if they did not sell off their A-film libraries promptly, rivals would beat them to the punch and saturate the market, each studio raced to sell off its top-line "vaulties" at premium rates. Within eighteen months of the R.K.O. sale, every major except Paramount had created prestige packages to be marketed on TV.[14]

A New Era: Old Movies on Prime Time Network TV

This changed the equation for the networks. In the days before the reissue of the Sherlock Holmes series, old movies had been the domain of local stations, whether affiliates or independents. The networks themselves wanted nothing to do with them.

As they saw it, it was a battle for control. Network executives like David Sarnoff and William S. Paley feared that film libraries made affiliates less dependent on network feeds, tempting affiliates to bypass expensive network programs to show low-cost movies that the local stations had licensed for themselves and could market to local sponsors [lots of them, as it happened] for greater profits.[15]

But now networks saw the potential for nationwide broadcasts of vintage films that could attract comparable audiences to the ones watching their famous variety shows and live dramas. And at less cost. So, while the Sherlock Holmes series, like other B-film products were permanently banished to late night shows and matinees, The Wizard of Oz, King Kong, Top Hat, Gunga Din and their successors found massive new audiences on network prime time.[16]

And what became of Holmes in the backwash? In a nutshell, he morphed. From a film personality showcased on TV, he became a TV personality reacting to his Rathbone film prototype.

Ronald Howard as TV's Sherlock Holmes

Today, the Howard-Crawford TV series is all but forgotten. But it is of interest both for its remarkable production history and as the first of the post-Rathbone Holmes incarnations. In it, the Universal formula was turned on its head – everything from the portrayals of Holmes and Watson to the Victorian settings and increasingly farcical-macabre stories were meant to stand in contrast to their predecessors.

In Howard's Holmes, the high-strung, moody, infallible

Rathbone gives way to an absent-minded, impetuous, and non-threatening youngster.

Even more remarkable is the new Watson: Bruce's boobus Britannicus transformed

to Crawford's astutus Britannicus. Crawford to this day remains the

unsung pioneer of the modern Watson as an intelligent, witty, and bemused

companion.

In place of Universal's twentieth century London, the TV series

returned Holmes to the Victorian era, making a point in the publicity campaign

of the care taken in reconstructing Baker Street and its environs. In fact,

the wonderfully detailed 221B sitting room was copied from the room Michael

Weight created for the celebrated Sherlock Holmes exhibit in the 1951 Festival

of Britain.[17]

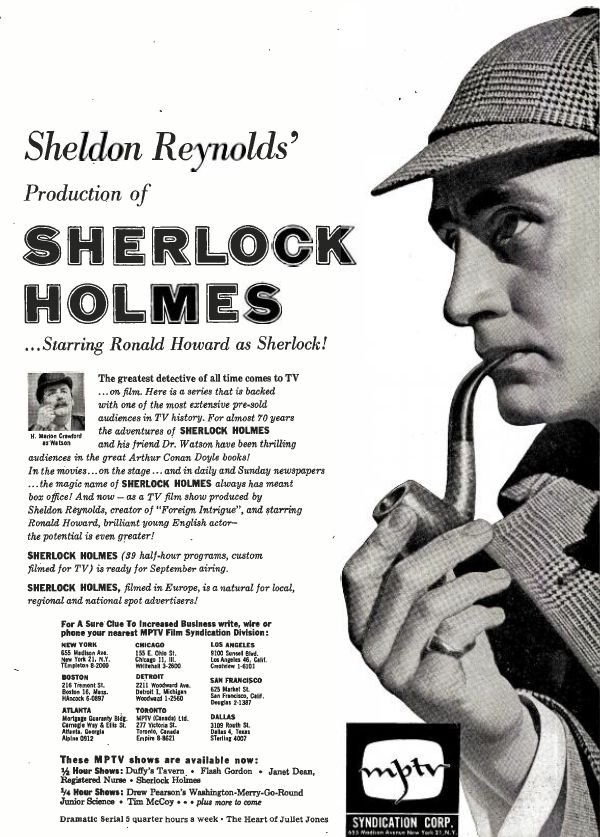

For Matty Fox, it was a natural progression. MPTV had become the market leader in the distribution of movies on television; now it was time to produce and market actual television programs. Sherlock Holmes followed with him. And so was born the first [and until Elementary, the only] American TV series to star Conan Doyle's detective.

Sheldon Reynolds Produces Holmes TV Series

By the time he underwrote the new Holmes program, Fox already had at least eight new teleplay series in the works, but Holmes proved his most expensive – and most lucrative – property. He contracted with Sheldon Reynolds, a young American producer to provide thirty-nine Sherlock Holmes episodes in seven months. The films were to be made at studios in the refurbished Éclair studios at Epinay-sur-Seine, with a French crew and a British cast of unknowns and faded veterans.[18] The series was then syndicated in the United States [but not anywhere else] over local stations.

"The Case of the Winthrop Legend," Sherlock Holmes MPTV, 20 Nov 1954.

An American producer, a British cast, and a French crew, filmed at the historic Éclair studio in Epinay-sur-Seine. The Baker Street set seen here was adapted from the one originally designed by Michael Weight for the Holmes exhibit at the 1951 Festival of Britain.

The series benefited from seasoned American directors and writers and from remarkable behind-the-scene French talent, produced on an historic sound stage. Sacha Kamenka, whose father created the legendary Russian-French Albatros Film Studio, was the stage manager who himself went on to stage manage for Hiroshima Mon Amour and Jean Anouilh's Le rideau rouge. Music was written by Paul Durand, the prolific composer and music arranger for Edith Piaf, among others. And the associate producer was Nicole Milinaire, one of television's first senior female executives, with a reputation for extraordinary efficiency and resourcefulness.[19]

So, Universal B-films gave way to Sheldon Reynolds' B-telefilms. Today we may be struck by the crude look of the Ronald Howard telefilms, especially when compared with the Rathbone productions. The Universals, though cheaply produced, ranked among the most handsome program pictures ever made. Here, fighting even greater budget restrictions plus the limits of 16mm photography and brutal shooting schedules [one 30-minute episode per every four-day week], the films looked quaintly unpolished.

Aside from the finely-detailed Baker Street apartment and hallway, the indoor scenery consisted of simple painted flats, indistinct manor rooms that could be re-used with minor adjustments, and an all-purpose cobblestone street set up inside the studio to be used with an all-purpose studio hansom cab. Dialogue scenes depended on the bland multiple camera technique that had become standard TV practice by the mid-1950s. Graphically this meant an endless series of choker close-ups, designed for efficiency, but not dramatic nuance.

Ratings and Reactions to Ronald Howard's Sherlock Holmes

However, this was not the perception of the series at the time. The first three episodes were particularly well received, even in the pages of The Baker Street Journal, and the ratings remained high throughout the first season. The series made headlines for the high prices sponsors were being charged. In New York, the Chase Bank was buying twenty-six weeks for $3,250; according to Billboard, among syndicated series only the Eddie Cantor Show charged more.[20]

Trade ad for Sheldon Reynolds' Sherlock Holmes, with Matty Fox's MPTV logo

Broadcasting 12 July 1954, p. 80.

Regardless. The series had difficulty finding enough sponsors to sustain a second season. Critics, notably Edgar W. Smith in the pages of the BSJ, lost their enthusiasm, and after a season-and-a-half, it ended.[21] By then – Fall, 1955 – Matty Fox was at it again. He mortgaged the Sheldon Reynolds series and sold off syndication rights to a consortium called UM&M, while he unloaded his Universals [along with the rest of his library] to the aforementioned AAP. Like Mr. Toad bouncing in his motor car, he leapt out of film distribution and TV production so he could now focus on his latest pet project: Pay TV. He would prove some thirty years ahead of his time.[22]

With Fox's departure, Holmes' adventures on syndicated television did not exactly come to an end. The Sheldon Reynolds series may have disappeared, but the Universals were endlessly recycled as they were licensed and sub-licensed to one distributor after another. Eventually they even came onto the 16mm educational market, the Universal logos restored. But not until PBS imported the Granada series, thirty years after the Rathbone TV debut, would Jeremy Brett provide Americans a new Holmes created for television.

The escapades that brought about the advent of Holmes' series on television may seem quaint and unnecessarily tortured, but in their day both the Universal reissues and the new Sheldon Reynolds series were shrewd, strategic ways of using the new medium to keep Holmes' memory green. In our own time, media distributors coordinate with services like Amazon, Netflix, and with media conglomerates like Turner Broadcasting and Time-Warner to promote old movies and new TV shows. But the end result is exactly the same: wheeler-dealer antics and quickly-made products co-mingle in a way to bring popular diversion for everyone. What Holmes said of the press in "The Six Napoleons," Matty Fox could say with equal force about television: "a most valuable institution if you only know how to use it."

Special thanks to David Pierce and John McElwee for their generous sharing of primary materials and invaluable critical insights. Thanks, also, to Jon Lellenberg for a sharp-eyed reading of the text and to Lou Luminick for sharing information about films on TV broadcast during the Second World War.

The first version of this paper appeared in Fan Phenomena: Sherlock Holmes (London: Intellect Ltd., 2014), 28-42. This website published a revised version In August 2016, and it was updated in September 2019.

Notes

[1] Or as filler in a vaudeville show. Sherlock Holmes Faces Death opened at the Chicago Oriental opposite a variety show that included Emmy's Madwags and Al Dexter and His Texas Troopers. In Manhattan, the Sherlockian double feature The Scarlet Claw and Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon backed "9 BIG ACTS!!" at the RKO Jefferson.

As Universal B-pictures, the

Holmes series kept colorful company on the screen. Most commonly, the films

were paired with exotic adventure pictures starring Maria Montez, Abbott &

Costello comedies, or horror films like Calling Dr. Death and The Mad

Ghoul. But not always. In New York Sherlock Holmes in Washington opened

on the Loews' circuit supporting a Judy Garland musical called Presenting

Lili Mars. In Chicago, Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror ran

with a re-run of Bambi.

[2]

John McElwee's blog, Greenbriar's Picture Show,

provides an excellent, informal overview of the labyrinthine directions both

the 20th Century-Fox and Universal Sherlock Holmes films took on television and

the theaters in the 1950s and beyond. <https://greenbriarpictureshows.blogspot.com/2010/01/confessions-of-unabashed-rathboneholmes.html>.

See Chris Steinbrunner and Norman Michaels, The Films of Sherlock Holmes, Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1978 for newspaper reviews of the Rathbone films during their

first run.

[3]

"How to Use TV Films Effectively," Sponsor 19 June 1950, p. 33.

[4] Before this, Holmes made a scattered easy-to-miss series of miscellaneous appearances. As early as 27 November 1937 NBC broadcast "The Three Garridebs" from its makeshift studio in Radio City as part of a variety program for the local American Radio Relay League's convention. Two years later, NBC followed with arguably the first Sherlock Holmes feature broadcast on television, albeit on its closed circuit station [W2XBS] -- UK's The Triumph of Sherlock Holmes with Arthur Wontner -- just as RCA was introducing the country's first commercial TV sets.

After commercial television established itself, NBC returned to Holmes on 25 March 1949 in "The Speckled Band" for its filmed half-hour anthology series Your Show Time. Holmes appeared in another one-off, this time broadcast live, on Suspense, CBS-TV's mystery series 26 May 1953.

The BBC series produced in 1951 with Alan Wheatley was never shown in the U.S.. McElwee [op. cit.] believes 20th Century Fox's The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939) may have been surreptitiously televised prior to the Universals by Hygo Television Films, but this has not been confirmed.

For NBC's private broadcast of "The Three Garridebs," see "Shadowing a Sleuth," New York Times, 28 May 1953. For the one-shot 1939 Wontner telecast, see television listings in New York Times 9/3/39, p. 27; New York Times 9/3/39, p. X8; and Herald Tribune 9/8/39, p. 40. For

more, see Peter Haining, The Television Sherlock Holmes (W.H. Allen, 1991), 44-49, 93-97.

[5]

The broadcast of the Wanger and Selznick films is at the heart of the complaint

launched by exhibitors against TV distributor Film Classics, Inc.,

cited in Eric Hoyt, "Hollywood Vault: The Business of Film Libraries

1915-1960." Diss., USC. May 2012, p. 213. The titles are named in Blair

Davis, "Small Screen, Smaller Pictures: Television Broadcasting and B-Movies

in the Early 1950s," Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television (23/

2) June 2008, p. 226; but Davis errs in assuming the TV exhibition was directed

by Selznick and Wanger. Their companies had dissolved during the war and had

sold off all rights ["Film Classics, Inc., Acquires Selznick-Whitney

Prints, New York Times 19 July 1943, 21].

[6]

David Pierce, "'Senile Celluloid:' Independent exhibitors, the major

studios and the fight over feature films on television, 1939-1956," Film

History (10/2), 1998, pp. 147-148.

[7]

Broadcasting 19 Apr 1954, p. 34, 36. For the sale of the series to

KTTV, Walter Ames, "Sherlock Holmes Films Sold to KTTV," Los

Angeles Times, 13 April 1954, p. 26; and Broadcasting, 19 April

1954, pp. 34, 36; for the sale to Cincinnati, Billboard, 8 May 1954, p.

5; for the sale to Tijuana, Billboard 22 May 1954, p. 7.

[8]

McElwee to author, 23 July 2013. Tillmany to author, 10 June 2016. In

mid-1954 Paramount sold their eight Bulldog Drummond features to Congress Films

for re-release, and then erased all evidence of ownership. Jack Tillmany's "My

Trivia" note to Bulldog Drummond Comes Back (1937) on IMDb

traces the Drummond series on TV and shows the consequences of Paramount's

abandonment.

[9]

Mulvey's June 11, 1954 agreement with Universal Pictures is cited in Pierce, fns.

48-49, p. 161. Mulvey, it should be noted, was not acting on behalf of Goldwyn

[who had a strong aversion to television], but was buying the films for

himself, parking them in his holding company, Champion Pictures, Inc. The

broadcasts in Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago were reported, respectively,

in The Philadelphia Inquirer television listings, 8 May through 20 Nov

1954; in The New York Times television listings from 9 Sept 1954 through

30 May 1955; and in the Chicago Tribune television listings from 2 Nov

1954.

[10] Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon and The Secret Claw were the only two of the Universal dozen officially reissued by Realart, and for most markets were the last Rathbone-Bruce films seen in theaters. There were unexplained exceptions, though, especially in smaller markets.

The best account of Matty Fox's

frenetic career is Eric Hoyt's chapters on Fox in "Hollywood Vault."

See esp. 235-251, 299-331 For Fox's masterminding Universal's deal with Realart,

Hoyt, 235-251, and Pierce, 148-150. Pierce speculates that the other ten

Rathbone Universals were withheld from the Realart deal because of story rights

complications. Withholding them from Realart simplified Universal's subsequent

selling off the properties outright. [Pierce to author, 6/30/13].

[11] For Matty Fox's involvement with the Sheldon Reynolds series, Lew Blumberg, "Total Recall," in Fridays With Art, ed. Dick Woollen, (Burbank, CA: Parrot Communications, 2003), pp. 353-355, though this should be used with extreme caution.

Nicole Milinaire, the

associate producer of the Howard-Crawford Sherlock Holmes series, writes about

her encounter with Matty Fox, "[who] did most of his business in bed and

hated wearing clothes. " See Nicole Nobody: the Autobiography of the

Duchess of Bedford (London: W.H. Allen, 1974), 155-156.

[12] Cited in "Terror By Night," Story File 3709, in summarizing the agreement between Denis P.S. Conan Doyle and Universal Pictures Company, Inc, 24 February 1942. The story file for "Pursuit to Algiers," signed the same date, with identical provisions, is quoted in Pierce, "'Senile Celluloid," fn. 48, p. 161.

Universal was also

contractually obligated to destroy its negatives to its serials based on King

Features materials, including Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, and Don

Winslow of the Navy. Happily, it did no such thing and through Matty Fox's

machinations made their way safely onto television. David Wolper, Producer (NY:

Scribner, 2003), 19-20.

[13]

The R.K.O. sale to Thomas O'Neil has been widely studied. For recent analysis,

Hoyt, "Hollywood Vault," 308-331 and Pierce, "'Senile Celluloid,'"

156-57. For an insider's account, Blumberg, "Total Recall," 357-59.

[14] For a succinct account of the snowball effect of the R.K.O. sale, Michele Hilmes, Hollywood and Broadcasting (Chicago University Press, 1990), 160-163. The best account of MGM's unique marketing of its old films on television is John McElwee's fascinating two-part essay, April 2012:

<https://greenbriarpictureshows.blogspot.com/2012/04/thirty-seconds-over-l.html>

<https://greenbriarpictureshows.blogspot.com/2012/04/thirty-seconds-over-l_28.html>.

[15]

The fullest account of network battles versus the stations is Hilmes, Ibid., 163-66.

[16]

ABC was the first network to broadcast a series of old films nationwide on

prime time, starting with A-list British imports. Cf. Variety advert.,

7 Sept 1955, p. 41. In spring, 1957 ABC expanded its series to include RKO

films culled from the C&C Television package. Cf. advert., LA Times, 7

April 1957, p. H7, and Chicago Tribune, 7 April 1957, p.

N16. For the outcome of the networks' decisions to screen movies

nationwide on primetime, Hilmes, Hollywood and Broadcasting, 166-167. Also,

Edwin Schallert, "TV Poses Deadly Threat to Movies," Los Angeles

Times. 2 Feb 1958, p. 20.

[17]

Ruth Voboril provides the source for the information about Reynolds using

Michael Weight's Baker Street set, originally designed for the 1951 Festival of

Britain [and now on exhibit at the Sherlock Holmes Pub on Northumberland Street

in London]. Unhappily, Voboril's website devoted to Ronald Howard and the

Sherlock Holmes TV series has been taken down. Michael Weight is uncredited in

the films themselves; the official series designer was the veteran French art

director Raymond Druart.

[18]

Production information on the Sheldon Reynolds series is scanty. Extended

international production credits for the crew derive from the internet,

including IMDb. Blumberg, "Total Recall," and the Ronald Howard

article reproduced in Voboril [op. cit.], are almost entirely anecdotal

accounts.

[19]

For Milinaire's resourcefulness, Blumberg, "Total

Recall," 358. For Milinaire's involvement with the Sherlock Holmes series

and "Shelly" Reynolds, Milinaire, Nicole Nobody, 145-152,

160-165.

[20]

For ratings, "The Top Ten Films in Top Ten Markets," Broadcasting 13

June 1955, p. 35 and 9 May 1955, p. 35. For sales, Billboard, 27 Nov

1954; 28 May 1955, p. 10.

[21]

For Edgar W. Smith's gradual disillusion with the series as it became more

farcical, compare his lyrical editorial review when the series debuted, in The

Baker Street Journal, 4/4 (October, 1954) 248-250 and BSJ, 5/1

(January 1955), 57-58, with subsequent comments: BSJ, 5/4

(October 1955), 244; and 6/3 (July 1956), 184.

[22] UM&M, in turn, would sell rights for syndicating re-runs for the Sheldon Reynolds series to MPTV's successor, Guild Films, in 1956. For an astute overview of the obstacles confronting pay TV, Hilmes, Hollywood and Broadcasting, 120-125. For a sympathetic assessment of Matty Fox's pay-TV scheme, Hoyt, "Hollywood Vault," 275-277, 342-44.

As for the Universals, the

labyrinth continued. AAP sold them to United Artists in 1957. For a summary

of their post-1950s travels, Greenbriar Picture Show blog, op. cit.

Russell Merritt teaches in the Film and Media Department at the University of California, Berkeley, and has published on D.W. Griffith, melodrama, animation, American and European film history, and Sherlock Holmes. He was associate producer on the restoration of the 1916 William Gillette Sherlock Holmes film. <russmer41@gmail.com>

Listen to his reminiscences about the Baker Street Irregulars and other Sherlockian matters.

Russell Merritt retains the copyright of this paper, and is solely responsible for the views, content, and images included with it.

An in-depth analysis and review of the Rathbone Holmes movies by Amanda Field

A Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes Film Festival at the Stanford Theatre

The Year's Best Sherlock Holmes Movies on DVD & Blu-Ray

The Best Sherlock Holmes Stories

Vers. 2.0d-RN Original work

Copyright ©2019

Randall Stock. All Rights Reserved.